I’ve avoided talking about why I left evangelical Christianity for almost ten years.

At first, a big part of me thought it would go away - I wasn’t even really sure that I was leaving.

Then, I didn’t write anything because I didn’t have any clear answers (still don’t, really).

When the “deconstruction” movement happened online around the pandemic, it seemed like there was no point. Everyone else was already pointing out the obvious flaws of racialism, anti-intellectualism, and a toxic marriage to politics. I didn’t feel like I had anything to add.

Finally, I was ashamed. The evangelical community isn’t well known for being super understanding about people having different opinions. They don’t burn people at the stakes anymore, but that might be because of the price of stakes in this economy.

August 9, 2014

It’s weird to know the exact date that your faith started to crumble.

Is “crumble” the right word? I feel like “reorganize” might be better.

See? I still don’t have answers.

I know that date because it was the day Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, MO.

Brown was walking in the street with a friend when officer Darren Wilson stopped him.

A struggle ensued between Wilson and Brown, and Wilson shot Brown six times - the fatal shot from 35 feet away.

From the time that Brown entered the street to the time he perished in front of his grandmother’s house, there are many conflicting eyewitness accounts, but the end result was the same:

A 29-year-old white police officer shot an 18-year-old Black college student to death in broad daylight.

To be honest, while I was drawn in by the early narrative that Brown had died with his hands in the air begging the officer not to shoot, I spent enough years soaked in conservative Christian culture that I hoped for justification.

At 6’4” and nearly three hundred pounds, Brown cut an imposing figure, even if he was just about twelve weeks out of high school.

Brown had stolen cigars from a convenience store minutes before and was now walking down the middle of the street, blocking traffic.

Wilson, looking for the shoplifting suspects, called for backup before he even stopped Brown and his friend Dorian Johnson.

A crime had taken place in the middle of the day, and two large youths were parading down the street in a troubled part of town like they didn’t have a care in the world.

Wilson’s wife had recently found out she was pregnant, with the baby due in March. He wanted to come home safe from work, so he called for backup.

The justification narrative started to take shape.

Brown had reached into Wilson’s car and struggled with him.

“Why can’t they just comply?” the old refrain sounded.

Like Trayvon before him, it felt tragic and senseless but avoidable. (This was before I knew more about Trayvon Martin’s case.)

Still, as protests raged, and riots ignited, the cries of “Hands up! Don’t Shoot!” clashed against the clean justification I had hoped for.

Ferguson

Ultimately, it was a Washington Post article “How Ferguson Became Ferguson” that disabused me of my wish for justification.

Look, I know that my Black friends will read this and say, “How could you hope for justification for the shooting?” I know that reading that will pain them.

But that’s because they have lived and known what I didn’t at the time.

Growing up the son of an immigrant from India, I obviously knew that I was a person of color.

Since 9/11, even with TSA PreCheck, I still receive “enhanced screening” about 50% of the time that I fly. (Four times through security this year so far, two of them I’ve been stopped . . . right on track.)

But I also knew that we weren’t Black.

In the ‘90s, my parents forbade my brother and me from sagging our pants like the Black kids on TV, and we weren’t allowed to listen to rap - unless you count the Christian band dc Talk as rap.

There was nothing we could do about being colored, but we didn’t have to be Black.

I now know that this is a common sentiment among non-Black minorities in America: “If you can’t be white, just don’t be Black.”

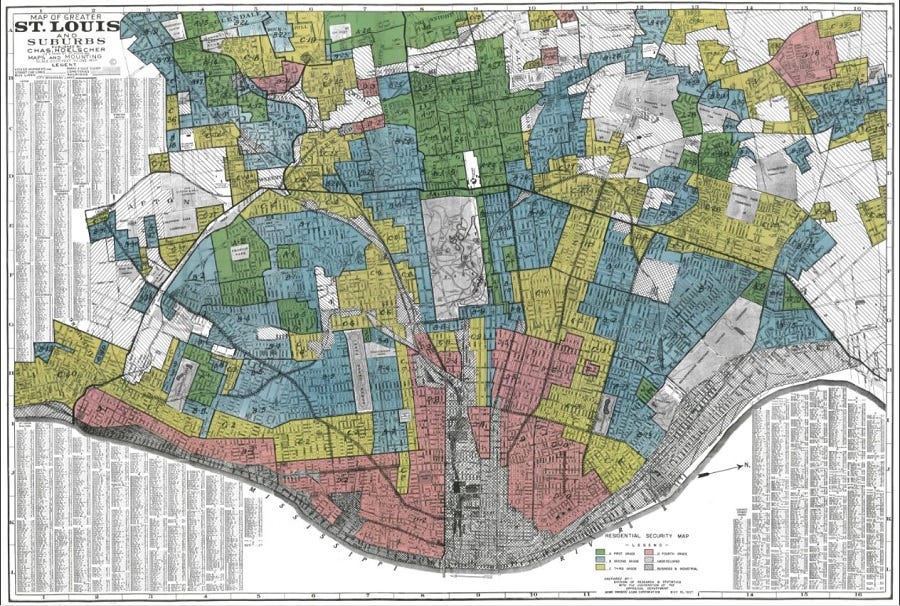

In the Washington Post article, I learned about redlining for the first time.

Redlining was the federal government practice of refusing home loans to people who lived in predominately black or brown neighborhoods. (Here’s a five minute primer from Harvard on redlining.)

The practice was not only legal but actually standard practice in federally-backed mortgages until The Fair Housing Act in 1968.

For communities like Ferguson, the Fair Housing Act came too late.

Imagine you were a Black doctor in St. Louis in the 1950s. You came back from serving in World War II, went to school to become a physician, work hard, and you make good money.

But, you don’t make enough money to buy a house in cash - who does? Not only that, even if you had the money, real estate agents won’t show you houses in white neighborhoods - for fear that those property values will go down, and those neighborhoods will be redlined.

In fact, even if you found a fair-minded white family to buy a house from, some house deeds include provisions that those properties could never be sold to a Black person.

So now, you as a Black doctor have to live in a Black neighborhood where no one can get federally-backed mortgages.

Predatory lenders set up shop, and even if you can manage your way through that gauntlet, it doesn’t mean your neighbor, the Black plumber, can.

Home ownership rates plummet in Black parts of town. The number one asset in most families’ portfolios is denied to Black families.

Then come the zoning laws that give tax breaks to factories that are investing in “blighted” parts of town.

What neighborhoods should we put freeways through? The ones that are mostly made up of renters, not homeowners, of course.

And when a neighborhood is pressed down and divided, crime begins.

Crime in inner cities isn’t a Black or white thing. It’s a desperate and deprived thing. Suicide bombers in Gaza are not fundamentally different from gang members in St. Louis, and neither of them are all that different from violent opioid dealers in rural Kentucky.

Same struggles. Different colors.

Justice

Seven months after Michael Brown’s death, the Justice Department released a report on Ferguson’s civil rights violations.

67% of Ferguson’s population was Black.

85% of vehicle stops were Black drivers.

90% of tickets were to Black people.

93% of people arrested were Black.

Black people were twice as likely to be searched even though they were found to be 26% less likely to be carrying anything illegal.

Again, only 67% of Ferguson’s population was Black.

But 95% of tickets issued for walking in the street were given to Black people.

And, crucially, 88% of police officer use of force was against Black people.

If you were Michael Brown, a teenager who knew you’d just done something wrong, walking down the middle of the street like any kid who thinks he’s going to live forever, and you got stopped by a police officer in Ferguson, what would you do?

If you knew that you were 20% more likely to have force used on you, that your odds of being beaten were actually greater than a roll of the dice, if you’d seen parents, grandparents, and friends unjustly targeted in your short two decades on this planet, would you have been level-headed enough at 18 not to do something stupid?

Darren Wilson was exonerated of wrongdoing in two different trials.

Was the shooting justified from a fair policing perspective? Two different juries found reason to believe it was.

But was the shooting justified?

No.

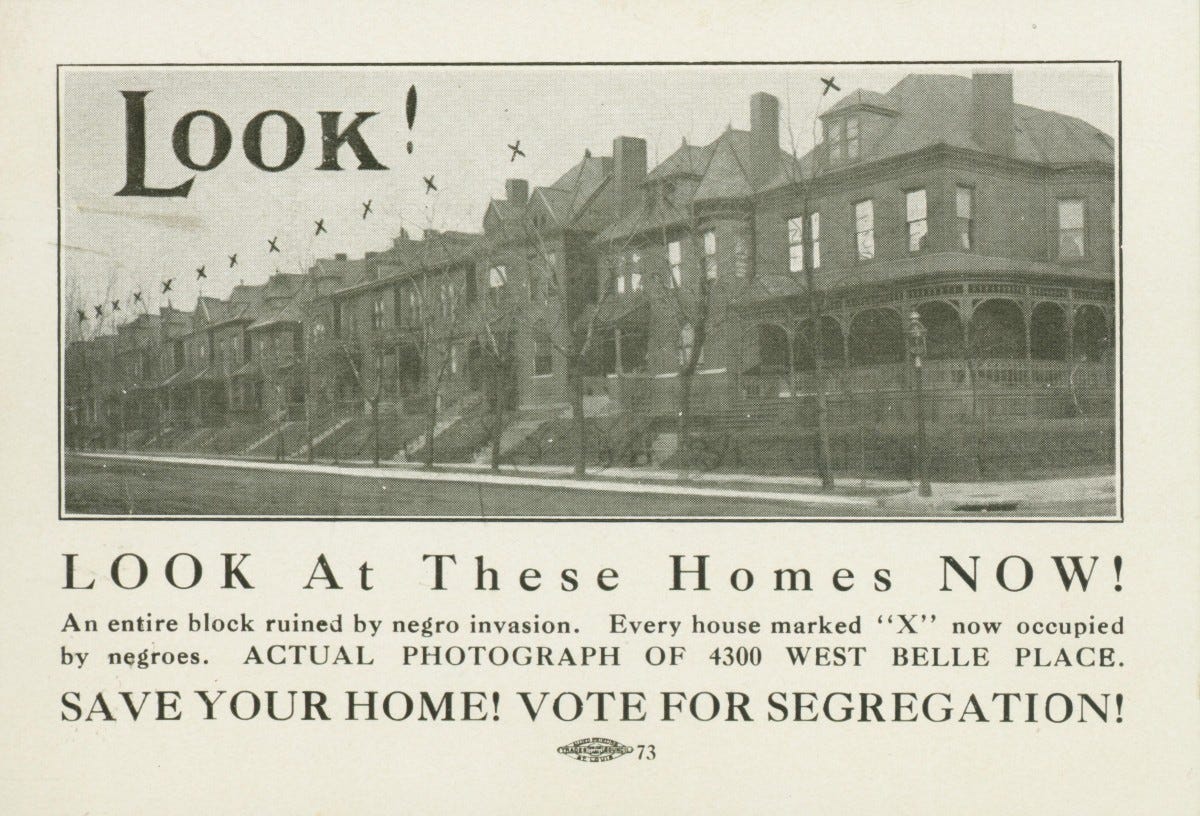

The racist policies that destroyed the wealth, social mobility, and political clout of the same group of people that had been kidnapped and violently forced to work unpaid in this country for centuries were not just.

The ghettos that we prefer to imagine are the result of moral deficiency were unjustly created, and they’re only full of Black people because we engineered it that way.

On February 27 of this year, because of Ferguson’s civil rights violations in over-policing Black residents, a federal judge approved a $4.5 million settlement for people who were jailed because they could not pay their fines and tickets.

Jennings, MO, a neighboring suburb, settled a similar class-action lawsuit about seven years ago.

The class action in Ferguson was filed six months after Michael Brown’s death, and the city fought it for nine years.

Faith

So what does this have to do with my personal faith?

I grew up being taught, and believing, that our Founding Fathers were Christian men who established a country on the principal that all people were created equal by God.

In this country, it didn’t matter where you came from, you had equal opportunity to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

When I was 12 years old, a newly baptized Christian, an elder at our church stood before the congregation and asked us to pray and fast that the deeply immoral Bill Clinton would not be reelected as president of the United States - partly because he had “relations” with an intern, but more importantly because he supported abortion.

We were reminded of the [completely out of context] Scripture, “if my people, who are called by my name, will humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and I will forgive their sin and will heal their land.” (2 Chronicles 7:14 about Israel, drought, pestilence, and plague.)

It was the first time I had ever fasted.

It didn’t work.

For me, like many evangelicals, God, country, rightness, and morality were all ingredients in the soup of our faith, inextricable from each other.

And even worse, all these years later, I was an ordained pastor, so my life’s calling and professional livelihood became part of that soup as well.

When Michael Brown died, unarmed, on the street in front of his grandma’s house, pouring blood out of six holes in his body, perhaps the perpetrator of a petty crime, but definitely the victim of a system that had been brutally engineered against him, the narrative that defined my life, my work, and my values began to break.

And that was just the beginning of it . . .